Here you can find Jerry Cohen's many stories about his career in developing the field of Chinese legal studies and his encounter with Asia. These stories are part of his upcoming memoir. His video memoirs "Life, Law and Asia" (a total of 16 chapters) are also available here.

Establish Yourself at Thirty: My Decision to Study China's Legal System in 1960

Jerome A. Cohen, Chinese (Taiwan) Yearbook of International Law and Affairs, Volume 33 (2015).

“ “Sanshi erli!” I first heard this famous Chinese phrase before I could understand it. Every educated Chinese knows it as one of a series of maxims coined by China’s greatest sage, Confucius, as advice appropriate to life’s successive decades.

I was about to turn thirty and confronting my most daring career decision. As a young, untenured professor of American public and international law who had just finished his first year of teaching at Berkeley, should I take up an extraordinary opportunity to study China, one that I had failed to persuade others to pursue?”

孔杰荣,三十而立:1960年的我是如何投身中国研究的,金融时报中文网,2017年3月2日。

““三十而立”!我第一次听到这句名言时,还不明白其中的意味。每一个受过教育的中国人都知道这句话,它是中国最伟大的圣贤孔子对于人生各个阶段应有如何作为的谏言。我即将三十岁,面临我职业生涯中最大胆的选择。作为一名年轻、尚未获得终生教职的美国公法与国际法学者,我刚刚结束了在加州大学伯克利分校的第一年教学,我是否应该接受一个非同寻常的——但我却无法说服任何人愿意接受——研究中国的机会呢?”

Preparing for China at Berkeley: 1960-63

Jerome A. Cohen, Center for Chinese Studies, University of California, Berkeley

“The University of California at Berkeley was a wonderful place to start learning about China in 1960. Of course, China - the real thing - would have been more exciting, but that option was not on the table. Soon after I began the long course of study required to understand the Chinese legal system, I actually wrote letters to both Chairman Mao Zedong and Prime Minister Zhou Enlai telling them of my quest to study the contemporary Chinese legal system and asking for the opportunity to visit the Promised Land. I never received a reply and supposed that they were too preoccupied with their angry correspondence with Khruschev and the Soviet Union to take on any new pen pals. ”

Hong Kong in 1963-4: adventures of A Budding China Watcher

Jerome A. Cohen, Hong Kong Law Journal, Vol. 47, Part 1 of 2017.

“I made the decision to study Chinese law and government in 1960 without ever having been to Asia. For a variety of practical reasons I had decided to spend the first three years of my four-year Rockefeller Foundation grant preparing for China at the University of California (Berkeley), where I was a young law teacher. Although I could have profitably spent the next year studying in Taiwan, I always intended to spend the fourth year of the grant getting as close as I could to the “real China”, the People’s Republic, which was still forbidden to Americans. So I decided to take up residence in Hong Kong unless the opportunity arose to live across the border in the Mainland itself. ”

The Universities Service Centre for China Studies – Present at the Creation

Jerome A. Cohen

Establishing the Universities Service Center

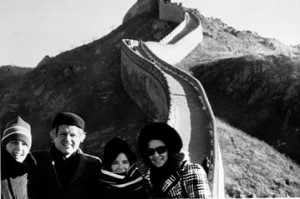

The Universities Service Centre's first Director Jerome Cohen and his family

Establishing a research center on the border of what was still called Red China or Communist China was a delicate undertaking because the British colonial authorities, always concerned to avoid offending the Mainland government, were carefully scrutinizing the preparations for the USC. They kept admonishing Bob Gray, a nice New York foundation executive who was not familiar with China or Hong Kong, but who had been sent out to set up and direct the Centre, to move slowly. Actually, the Brits seemed to suspect that the Centre was going to be a CIA front for China-watching or at least that a few of its American scholars might be connected to “the Agency”. Carnegie was apparently so sensitive to the British concern about China-watching that it made the name of the new organization the innocuous-sounding “Universities Service Centre” without indicating what the focus of its work would be. From the name alone, the uninformed might have mistaken the Centre for an auto repair shop! It was not until 1993 that the words “For China Studies” were added to the name.

USC:中国研究往事

USC创始主任、纽约大学法学院教授孔杰荣(Jerome A. Cohen), 金融时报中孔文网, 2015年2月6日

“在当时还被称为“红色中国”或“共产主义中国”的边境上成立一个研究中心,是一项微妙的工作,因为英国殖民当局总是担心触怒内地政府,所以对USC的准备工作审查得非常仔细。他们一直告诫为人不错的纽约基金会主任Bob Gray要慢慢来。Gray对中国和香港都不太熟悉,但是被派到香港设立和主持这个中心。实际上,英国人似乎怀疑中心会是美国中央情报局(CIA)为观察中国所设立的前哨,或者说,至少里面的几位美国学者可能跟CIA有关联。卡耐基基金会显然心领神会英国人的担忧,以至于给新组织起了一个听起来无可非议的名字,叫“大学服务中心”,并没有点明该组织的工作重心。光看名字,一般人不知情,很可能会错把中心当成一个汽车维修店!一直到1993年,“中国研究”这几个字才被加了上去。”

Ted Kennedy's Role in Restoring Diplomatic Relations with China

Jerome A. Cohen, Journal of Legislation and Public Policy, May 17, 2011

Ted Kennedy and his family visit China in December 1977

“In the crucial period of 1966–79, as the American people were developing a new image of China and considering a new policy toward it, Ted Kennedy played a significant role, albeit one that is now little understood or remembered. That role partially played out in public, and some of it took place behind the scenes. I cannot give a comprehensive account of this story, which would make a splendid master’s thesis for a budding political scientist. But I know a good deal about it, since I helped advise Ted on China during this period. Although memory fades on certain details after almost half a century, many vivid events seem unforgettable.”

My First Trip to China: “The Missionary Spirit Dies Hard”

Jerome A, Cohen, Hong Kong Economic Journal, September 3, 2011

(This article was published in the Hong Kong Economic Journal on September 3, 2011, online as part of the “My First Trip to China” series.)

Jerry and Zhou Enlai, 1972

“I started studying the Chinese language August 15, 1960 at 9 am. Confucius said “Establish yourself at thirty,” and, having just celebrated my thirtieth birthday, I decided he was right. I would not be allowed to visit China, however, until May 20, 1972. For almost twelve years my study of China’s legal system and related political, economic, social and historical aspects, had necessarily been second-hand, dated and from afar. It was a bit like researching imperial Roman law or deciphering developments on the moon.”

China’s Changing Attitude Towards International Law, in Hungdah Chiu, China, and International Law: A Life Well Spent”

Jerome Cohen, Maryland Journal of International Law, Vol. 27, Issue 1 (May 2012)

“On June 16, 1972, I had the good fortune to have dinner with Premier Zhou Enlai. I sat on his left and John Fairbank, the great historian of China, sat on his right. We were both from Harvard and had been members of a Harvard-MIT faculty group of China specialists who, immediately after Richard Nixon‘s 1968 election, had given the President-elect and his new assistant, our erstwhile colleague Henry Kissinger, a memorandum proposing steps towards a new American policy toward China. During our 1972 dinner with Zhou, we tried to persuade him to start the process of cultural exchange that we had recommended by permitting Chinese to go to Harvard. Zhou was interested, but he thought it was premature in the absence of formal diplomatic relations. He cleverly sparred with us on this and other topics. Finally, near the end of the dinner, I decided to go off on a different tack. I said to Zhou and to the group of Chinese officials around the table, including his deputy foreign minister, Qiao Guanhua, ―Now that you‘re in the United Nations, you should put somebody on the International Court of Justice. They thought that was the funniest thing that anybody could ever suggest. They thought I was a comedian! What a ridiculous idea that the PRC would want to put someone on that bourgeois institution, the ICJ, where the Chinese representative would surely be outvoted and perhaps not even treated fairly. Their response reflected not only their Communist orientation, but also the distrust that many East Asians have felt toward Westerndominated international tribunals since international law came to East Asia in the latter half of the nineteenth century.

It took a decade, but in 1982 the PRC finally nominated a leading Chinese jurist for the ICJ. Since then, a succession of Chinese judges have done respected work on that court. However, the process of PRC participation in international adjudication is not complete. Like the United States, China has not accepted the compulsory jurisdiction of the ICJ, nor has it accepted participation in the relatively new International Criminal Court, although it has placed capable representatives on certain ad hoc international criminal tribunals.”

Law and China’s “Open Policy”: A Foreigner Present at the Creation

Jerome A. Cohen, American Journal of Comparative Law (forthcoming 2017)

Abstract:

This is an account of my experiences in China during the years 1979-81 when I had the opportunity to participate in the re-establishment of a largely Soviet-style legal system following the end of the Cultural Revolution. It describes my two years of teaching foreign direct investment law and international business law generally, including dispute resolution processes, to Beijing city officials charged with the responsibility of negotiating trade, licensing and joint venture investment contracts with multinational corporations. I also discuss my early experiences actually negotiating such contracts with Chinese officials on behalf of American and other companies and conducting special training programs for legislative draftsmen and administrators in the fields of taxation and investment law. In addition, I mention my related efforts involving translation and publication of emerging legislation into English, selecting the first Chinese officials to study law in the United States and giving occasional lectures in cities beyond Beijing.

孔杰荣,改革开放初期中外法律交流亲历记,金融时报中文网,2017年1月6日。

孔杰荣:1979-1981年是中国法治的历史性时刻。我愿意提供一个简短的回忆录,与大家分享参与这段历史的经历。

Glimpses of Lee Kuan Yew

Jerome A. Cohen, East Asia Forum, May 25, 2015

“Seldom has the death of a great Asian leader commanded as much appreciation in the West as the passing of Lee Kuan Yew. The mind numbs at the number of well-earned tributes to the man who led Singapore to become a successful and influential nation-state.

Despite the huge disparity in size and political-legal culture between Singapore and mainland China, many observers have emphasised the seductive attraction that ‘the Singapore model’ has held for Chinese communist leaders who are searching for a formula that will enhance China’s phenomenal economic development without sacrificing the Party’s dictatorial control.

Other writers have featured Lee’s intellectual brilliance, self-confident personality and deep understanding of world politics, which he freely dispensed to political leaders of various countries eager to bridge the gap between East and West.

A few early post-mortems have even transcended the natural tendency, in the wake of his departure, to minimise the costs of Lee’s accomplishments, especially his authoritarian policies and practices.

This essay will provide a bit of grist for the historian’s mill by offering an account of some fragmentary personal contacts that I had with Lee a generation or two ago.”

李光耀的新加坡:法治外衣之下

孔杰荣(Jerome A. Cohen), 金融时报中文网, 2015年5月26日

“鲜有亚洲领导人去世后能如李光耀这样获得西方世界如此多的赞誉。赞美之词多到不可思议,但对于这位名人,确实也是实至名归:是他将新加坡这样一块弹丸之地打造成具有世界影响力的成功国度。

纵使新加坡和中国大陆在地理面积和政治法律文化上有着巨大不同,许多观察者都强调,当中国领导层孜孜寻求一个既不牺牲共产党专政统治、又能保持经济持续发展的处方时,“新加坡模式”对他们有着诱人的吸引力。

有关李光耀的很多书作描绘了他的绝顶聪明、自信人格,和他对全球政治的深邃见解——在渴望弥合中西方鸿沟的各国政治领导人面前,李光耀总是很乐意分享这样的见解。

在他去世后不久,一些赞美他的文章甚至刻意淡化他成就背后的代价,尤其是他的威权主义政策和实践。

我写作本文的一个谦卑目的,是希望通过回忆数十年前我与李光耀的几次亲身接触,为历史学家的磨坊提供一点原始材料。”